Excerpt from Colonial Tales by Alessandro Spina

Posted by Darf Publishers, February 1st 2018

Translator’s Note

This middle section of Alessandro Spina’s The Confines of the Shadow: In Lands Overseas, is set in the nervously restless years prior to the outbreak of World War II, a time when the Italian colonists in Libya’s cities of Tripoli and Benghazi felt more confident than ever in their courageous industriousness as they attempted to refashion the inhospitable African land beneath their feet into a replica of their beloved motherland. A few exceptions aside, all the stories in Colonial Tales are set in Benghazi during the 1930s and early 1940s and – unlike in the other installments of Spina’s eleven-volume epic – all of the characters are Italian. Not a single Libyan makes an appearance here and that is the point: it is part of Spina’s pointed critique at colonial Italy’s refusal to even acknowledge its native subjects. Indeed, the Italians grew so confident in their unchallenged hold over the quarta sponda – or ‘fourth shore,’ squaring the Italian boot’s three other shores – over these years, that they officially annexed the province to Italy in 1939, by which time Italian settlers made up over a third of Libya’s urban population and owned extensive land holdings in the interior of the country. Those familiar with narratives of the British presence during the Raj will recognize the intimately theatrical scenes Spina sets for his readers as he chronicles an episode in Italian history that has been nearly obliterated from the country’s collective memory. Time stands perfectly still in Spina’s Benghazi while the ladies chatter and their husbands talk of war. The city’s wide avenues are dotted with cafés where people gossip and orchestras play, yet Spina’s narrators often take the reader on a tour of the surrounding area’s Greek ruins – the remnants of the once-powerful city-states of the Libyan Pentapolis. Spina’s tableau is vast: his stories feature haughty grande dames, industrialists, aristocrats, politicians, revolutionaries, servants, functionaries, prostitutes, dressmakers, policemen, school teachers, poets, musicians and knaves – whether in uniform or not. Nevertheless, this section of Spina’s epic rightfully retains a militaristic feel: after all, the military was in charge in Italian Libya, and as such, many of the stories are set in the Officers’ Club, where the soldiers sleep with one another’s wives, scheme against one another, stage one-man shows, eat, drink, philosophise and discuss Italy’s chances in the coming war, blissfully unaware that their artificial presence in that conquered land is soon to vanish entirely. As I mentioned in my introduction to Volume One of The Confines of the Shadow, Spina’s officers perfectly typify his concept of the ‘shadow’: their minds are haunted by the maddening darkness – or hollowness – of the colonial enterprise, and yet they are simultaneously unable to extricate themselves from it, bound to serve their masters – in this case the Fascist bureaucracy and its Supreme Leader, Benito Mussolini – until the bitter end. And bitter it was.

THE STOLEN MANUSCRIPT

Once he had finished reading the manuscript, the little professor – as they called him in the city, because he was blonde, thin, almost childlike, with a lock of loose hair always hanging over his eyes – placed it on the table. It was bizarre that that woman hadn’t seen anything but old age and death in that industrious Italian colony. She hadn’t written about his city, but rather about the colony’s capital – which lay roughly a thousand miles away; roughly because precise measurements were careless in Africa, and those spaces – the ruthless southern winds that seemed to want to obliterate everything in their path to restore the landscape’s primeval innocence – made any notion of precision nothing but wishful thinking, if not in fact ridiculous. Whenever he looked at the windbreak hedges outside, which had been planted to shield the areas of cultivated land and vegetable patches, his mind turned to the Justinian walls which had failed to protect the cities of the ancient Pentapolis[i] from the blind impulses of the tribes from the interior. Scorched by the sun, one could still tour their ruins along the coast: Ptolemais and Teuchira. All this appeared to justify the utter absence of joy in the author of the manuscript, now that, as she put it, war had been consigned to the winds and the barbarians: the Italian colony was on the verge of slipping away, of being hurled back into the sea.

The author had indulged herself, for example lingering on the almost ethereal receptionist at a hotel, a parody of the confident army officers, in his uniform and his incredibly pallid skin, as though he’d just emerged from a dream. Or the incredible story of a baroness who was on death’s threshold in some room, even though nobody was allowed to know which: people said one day a guest would place his hand on the wrong door handle and on entering would come face to face with death.

Her death.

Truth be told, the entire manuscript was riddled with sepulchral indulgences, which is rather natural when all is said and done, the young man thought, because it’s a kind of last will and testament: it doesn’t deal with any material possessions, but rather with the past, a past which that woman didn’t know who to entrust with.

***

She had been a friend of his mother’s, while in the other city, Tripoli. A city whose incredibly long history – the Phoenicians, the Romans, the Arabs, Charles V, the Hospitaller Knights of St John of Jerusalem, the Sultan, the Barbary corsairs, Count Volpi,[ii] all stood on that scene like in a kind of eighteenth century Singspiel[iii] – appeared to guarantee both its reality and its continuity, thereby devaluing the city he lived in, which was as intimate as one’s home, having been nearly conjured out of thin air by the industrious colonial government two or three decades earlier. However, surprises abounded whenever one tried to circumscribe a complex reality: the narrator knows that well, it resembles the confusion and embarrassment that a tourist guide experiences in a historical city where monuments crowd the proscenium like characters, all wanting to tell their own stories, which are often heartbreaking because they’re in ruins – and all the more seductive for that reason. It is difficult inside a theatre to obtain the silence of a librarian, where every book is like a cell where the prisoner inside is a mute.

Carlino sighed and smoothed back his hair, without touching it, simply by tossing his head back, as though turning the page.

He was a bastard, and thus a secret.

Whenever she went to see him, his mother would introduce him as one of her sisters’ sons, and nobody ever got suspicious. Especially in the colony, which filled with people from all parts of Italy, thus allowing them to reinvent their pasts: there was no such thing as a constrictive, collective, communal memory, just like in America, of which the North African colony was a mere parody, albeit only a stone’s throw from Italy’s doorstep, on the other side of the Mediterranean, or Mare Nostrum. The mother owned a dressmaker’s. Needless to say, there were three characters in this drama, naturally the secret familial nucleus, there was a father; a married man who’d had a long relationship with Teresa. He belonged to higher circles and was well-to-do. ‘Rather well-to-do,’ the malicious gossipers stressed. Carlino had no love for him: he was a despot, with a beast’s dangerous narcissism, as he would say. Teresa did nothing to adjust the father’s image in the boy’s mind – given that Carlino had after all barely seen him, and ever since he’d lived in the colony, for the past five years, he hadn’t seen him once.

Carlino was twenty-nine years old.

He was esteemed and respected by all at the secondary school on Via Fiume: he was steadfastly diligent in carrying out that ancient and noble profession. The students occasionally took advantage of him, they weren’t afraid of him. He hated to experience or inspire such a sentiment – fear – in anyone.

***

He had lain the manuscript down on the small iron table, which stood atop three curvy legs, and had lingered there motionless. At which point a German man with a grey beard, who had landed in the Italian colony to venture with a colleague towards the heart of Africa, where they intended to carry out geological surveys.

Geology is concerned with the origins of the Earth and its composition and structure as well as its history as it changes over time. Carlino, who taught mathematics and had never even heard of geology, the notion struck him as very curious and he told the German as much, which made the latter shudder – who nevertheless being courteous, smiled. It was funny. As Carlino knew German, he had offered to serve as their interpreter during the few days they would be in that coastal town to prepare their expedition along the old caravan routes of the desert. They were punctilious, they wanted to prepare everything, even though Africa tends to scoff at anyone who makes plans, just as it did with all those efforts to catalogue and ‘circumscribe’ everything, the mathematician ironically explained.

They were sat on Carlino’s modest veranda – which he’d erected at the back of his little villa, in the shade, under a sloping glass ceiling, a corner of Oriental taste: the divans were strewn with cushions, bleached mats on the floor, painted peacock feather protruding out of cloisonné vases, yellowish ostrich eggs decorated with leather trappings, as well as a whole assortment of Oriental knick-knacks on the walls. He had never managed to come up with a plausible explanation to himself – the others never asked him anything about it, since that kind of taste was particularly in vogue at the time – as to why he kept indulging himself in reconstructions which strived towards being museum-like but wound up being dreamlike instead.

The geologist, for his part, had been very taken with that corner, it was the complete opposite of the gargantuan natural structures that were the object of his studies. He had wanted to show it to his colleague and he had taken advantage of the situation to quote some nobles verses from the West–östlicher Divan.[iv] It was as though his soul had stumbled, just like our ears can sometimes hear strange, mysterious, elusive sounds: an unperceivable shadow had danced through his knowledge-cluttered mind.

Doctor Batisti, a friend of the little professor, appeared at the garden gate. He too wore a grey beard, which had been trimmed in the same style, leaving the two – the physician and the geologist – to look at one another somewhat embarrassedly, as though one was mocking the other. Yet neither truly knew who among them was the fake, and thus they both kept quiet.

The fact the Doctor didn’t know a single word of German brought some lightness to the situation. Carlino, who spoke to one first, then the other, felt like he was walking on two different roads.

‘Did you read it in the end?’ the physician asked, having noticed the manuscript on the table as he took a seat.

‘I finished it just a moment ago.’

‘Was I indiscreet in giving it to you?’

‘No,’ Carlino replied. ‘The manuscript was addressed to a person. Well, I am that person. I am Antonio’s friend…’

***

‘Let’s go back a few steps…’ he began, as though standing in his classroom, whenever they had to summarize a certain notion, the students’ memories suddenly became wobbly. ‘I first made the acquaintance of Mrs Manzi in Paris, several years ago. Having always been close to her, my mother finally convinced her to come in winter to the colony. The old woman appeared to be close to the end of the line, or was at least unable to avoid it. Nevertheless, Africa saves only whoever she wants to save, and is as inscrutable as Providence itself: it can seduce one, destroy another and bore a third… it hardly ever repeats itself and it laughs at all our plans, even the flamboyant ones our Generals cook up.’

The woman had lodged at the hotel, the Mehari, which was situated by the shore: a low, well-structured edifice, which looked as if it wanted to playfully and elegantly recreate the bazaar’s winding labyrinth. So long as she’d been able to walk, the old woman had dined at her friend’s house; later she did so at her hotel, a ship she could no longer abandon at will: amidst Africa’s blinding light it was slowly carrying her to her final port of call.

‘I’m disappointed that the manuscript was left unfinished: she had promised in her incipit that she would explain why she had felt the need to talk to me of all people, but she wasn’t able to do so. Time laughs at me while I wait for clarity on my own life,’ at which he stood up, as if he’d struck at the heart of the matter, or had wanted to impatiently emphasize, either jokingly or painfully, his appearance on the manuscript’s stage. The physician followed the words, while the scholarly German observed his movements, the former looked like he was in a library, the latter as though he were at a cinema – and they were both engrossed: ‘She wrote the manuscript for me because we both nourish unlimited ambitions for the people we love: a kind of violence that demands a theatrical intensity in life, which is the only plausible release one can experience, however ephemeral. The beloved is unable to be satisfied by any old plan, our love suffers because of it, as though it was devoid of justifications, derided, and even if it doesn’t perish, it never knows peace. All of this gave us a language, a system of values, reactions in the face of others’ victories or defeats. That woman was deluded by the four men in that drama, the husband and the sons – even handsome Antonio, whom she told me one time she hadn’t even been able to profit from his ruinous fall in order to grow. But let us leave that ghost alone, it’s an insatiable spectator and it is offended by the lives of others, indifferent to its torments, yearnings, just like nature, which has its own dramas, which are always independent from ours: didn’t you promise me that you would tell me how you managed to get your hands on that manuscript?’

The physician was astonished by the little professor‘s revelation, that he himself had been the intended recipient – every event results in a revelation – and thus that he would ultimately in his own way be a character in the manuscript’s narrative. ‘Easily done,’ he confided.

He instinctively stood up, while Carlino sat back down. The scholarly German stood there watching them without understanding anything, although he was far from embarrassed. The different languages had created scenarios that overlapped, just like the real and the unreal, sounds and sights, or the present moment and one’s memories. Perhaps he understood geology as a metaphorical science. Regardless, all he had to do was think that he was standing in front of animals that belonged to some odd, unclassified species, which was devoted to idle meanderings.

‘I bore witness to the agony of her death throes, in that colonial hospital,’ the physician said, ‘she’d shown up all of a sudden and there weren’t any of her relatives there: having been called from the motherland, they hadn’t had time to get there yet, the mail boat operated according to fixed schedules that were indifferent to all the (occasionally hurried) tragedies of human affairs. The old woman was nearly immobilized, but I had the distinct impression that using her hand or her eye – don’t ask me how, when reality has reached a turning point one can’t take note of everything – she would start to fiddle around with her diary: I should have hidden it.

‘Maybe I made the entire thing up: but one page I read, almost without realizing it, and maybe some phrase that was specifically directed at me, which foreshadowed the rest of the text, convinced me that she hadn’t written her diary for her husband or her sons, and that they couldn’t be allowed to get their hands on it. It might be true that it hadn’t been written for me either, but a stranger is in a privileged situation whenever one looks for a confidant, and can provide a confidential service: I took the diary without bothering to conceal my actions and stuck it inside my bag. From that moment on, the unhappy woman never looked at me again. Four days later, her family arrived, the father and his three sons, but by then she had slipped out of consciousness.

‘So what should I do now? Should I return the manuscript to them?

‘Having placed it in your hands, I feel relieved of any sins of indiscretion, it’s as if you were the one responsible for the theft now. At least… what I mean… that my good cheer comes from the fact that I fulfilled the mission, however casually, by placing the diary in the hands of the person it was destined for. Keep it, burn it – or hand it over to your German mentor over there.’

The geologist nodded with his head, possibly because the physician was looking at him.

Only then, having regained his calm, did he ask what had happened – and he pointed his finger at the manuscript, having understood that the real story lay in there, and not in the conversation between the two friends.

Carlino tried to sum up the entire affair, but whether he was distracted by other thoughts, since it was difficult to tread slowly when the past transforms itself and returns with all the violence of the wind, or perhaps the geologist had remembered an unresolved detail from the trip, the German had therefore mistaken one thing for another: an old woman had died, and this lady – which the manuscript mentioned, where maybe a last will and testament had been concealed, not once concerned with worldly goods, but with the interpretation of old, painful memories – had actually been the doctor’s own mother. He immediately stood up and offered the newcomer his condolences – who in his turn stood up, smiling and failing to understand why that distinguished gentleman, who wore a beard like his, was congratulating him.

Carlino didn’t translate a single word, and that was fine. After all, when the past returns, it enchants us and steals us away. Inside that manuscript was his own story, lost in the wake of others’ stories.

Now all that is left is to explain how so many different events can be interconnected.

***

Carlino’s mother and the manuscript’s author (as was to be expected, this was a story of disillusions, not that it had anything to do with love or money: that woman had unlimited ambitions for the destiny of others and none of the men in her life stuck their necks out or took risks; but she was wrong, there was something captivating about Antonio, or at least this was the opinion of the woman who had loved him for a while) were therefore not the same person: they were childhood friends. Just like how Carlino and one of the woman’s three sons, Antonio, had spent parts of their youth together.

This wasn’t what had misled Carlino, it had been a sentence which had slipped through the author’s fingers, perhaps her illness had reduced her faculties. She had therefore revealed that Carlino wasn’t the son of that industrious businessman who’d carried on a long-term relationship that everyone knew about, a man he hated – Carlino had in fact, her friends had confided in her, been fathered by an army officer with whom she’d had a brief fling, a man of whom she’d then never heard from again, there was little more to his memory than his uniform. It seemed like the same old story that rose out of a conquered town, when soldiers ran loose through the streets, having been given a free hand. An officer had come into her home, he had forced himself violently on her and then had vanished. In actual fact, the event had taken place in a hotel where the mother had been staying.

What truly embarrassed Carlino was the hate he’d nursed for that devastating father of his, with his beastly narcissism, who believed himself master of the entire universe, having confused the former for his factory: he had blamed an innocent man. Thus, he too had been betrayed in his turn: his real father was a uniform. His childhood drama was either absent or was headed for other destinations.

He could run over to his mother, erasing the thousand miles of distance that separated them, and ask to know more. But hadn’t she confessed to her friend, who didn’t seem to know much about it anyway?

What about him, the little professor, wasn’t he a grown up man after all?

What did it matter to men who their fathers were? Fathers are figures who belong to the world of infancy, of adolescence.

The geologist was observing his guest and nodding affirmatively with his head.

The physician looked at both of them and didn’t understand what had happened. It seemed as though the manuscript belonged to the two of them, and that he was being kept in the dark, the situation had been turned on its head.

‘Today,’ Carlino mockingly announced, ‘the little professor has died: the manuscript was my initiation rite, marking my passage from youth to adulthood: I will now begin my second life.’

The geologist didn’t understand what the guest had said about him, he had merely grasped the word professor, which was used in both languages.

[i] Pentapolis: informal league of five cities in the western part of Cyrenaica, named after Cyrene, the leading city of the Pentapolis.

[ii] Giuseppe Volpi, Count of Misurata [now Misrata] (1877–1947): Businessman who governed the colony of Tripolitania in the mid-1920s. He was also the founder of the Venice Film Festival.

[iii] German: ‘sing-song,’ a kind of opera.

[iv] West–östlicher Divan: (West–Eastern Diwan) a collection of poems by Goethe inspired by the Persian poet Hafez.

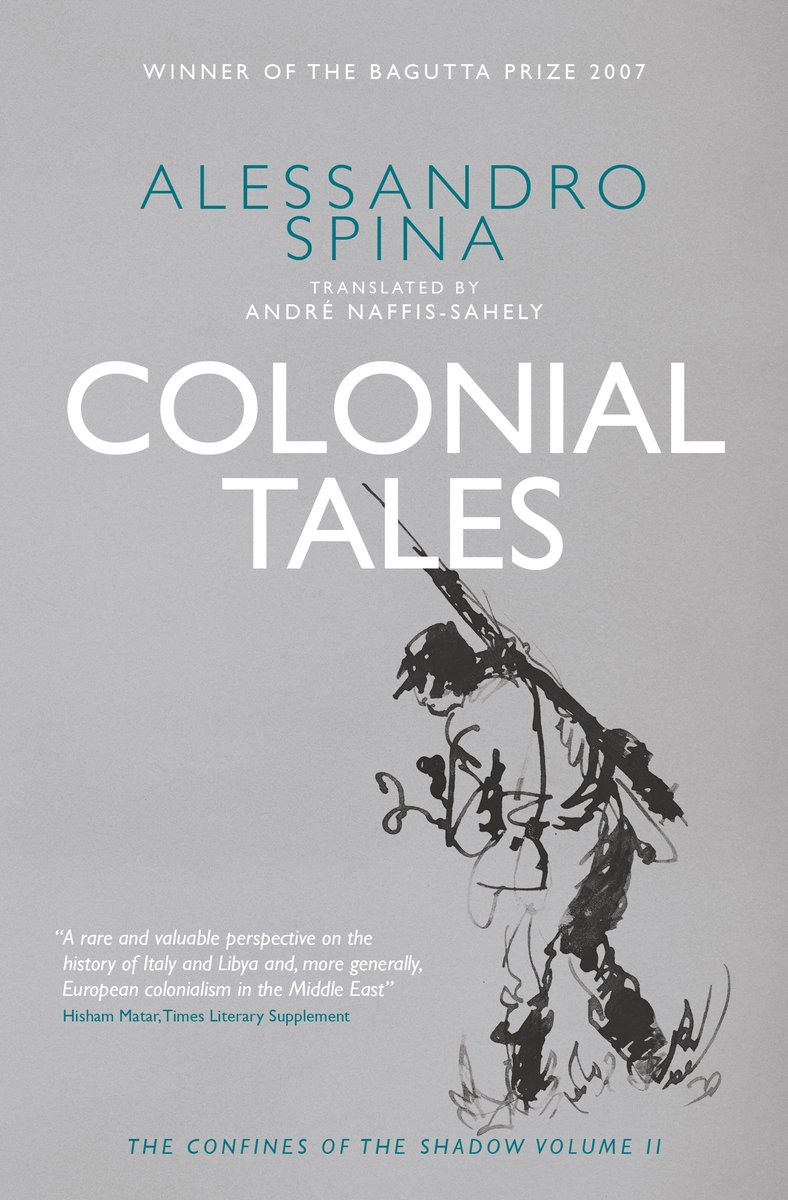

Alessandro Spina was the nom de plume of Basili Shafik Khouzam. Born into a family of Syrian Maronites in Benghazi in 1927, Khouzam was educated in Italian schools and attended university in Milan. Returning to Libya in 1954 to help manage his father’s textile factory, Khouzam remained in the country until 1979, when the factory was nationalized by Gaddafi, at which point he retired to his country estate in Franciacorta, where he died in 2013. The Confines of the Shadow (Morcelliana) was awarded the Bagutta Prize, Italy’s highest literary accolade, in 2007.