From Libya to London – the Evolution of Darf Publishers

Posted by Darf Publishers, December 14th 2017

“BOOKS were his passion, and they changed his life.” In 1952, Ghassan Fergiani’s father established his first bookshop in Tripoli. 25 years later, he would be confronted by the regime and driven out of his homeland and into the basement office at a Hampstead bookshop where his passion for literature would continue to blossom.

Mohammed Fergiani and his family moved from Gharyan to the Libyan capital in 1928. Upon arrival, they moved into a house with five other families, each with their own room. At age five, Mohammed was introduced to the literary world whilst playing outside his home in the Dahra district of Tripoli.

“A nicely dressed young boy walked by with a book in his hand,” Ghassan says. “My dad asked him, ‘What is that?’ ‘It’s a libro’, the young boy replied in Italian. He really liked the coloured pictures and text. After discovering it was from a school, my dad got it in his head that he wanted to go. After weeks of screaming ‘Scoula! Scoula!’ (Italian for school) to his parents they managed to secure him a place.”

Ghassan’s crisp recollection of the story points to the encounter’s significance not only to his father, but himself also. “He stayed in school for about six years where he learnt Arabic and Italian. At that time, six years was enough. He discovered his business mind, which enabled him to set up the bookshop and later move into real estate.”

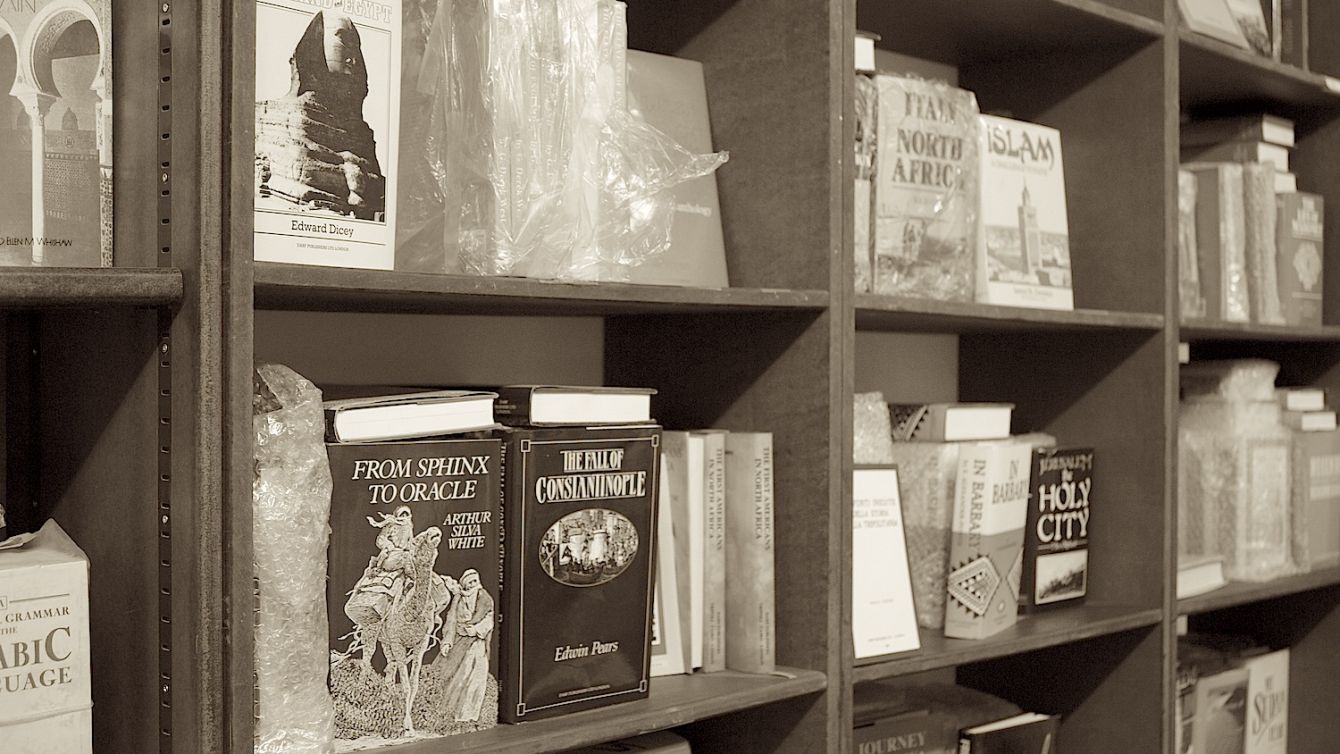

Dar el-Fergiani publishing house was born. Mohammed would use basic methods to print the works of Libyan authors by travelling back and forth to Egypt. “It wasn’t sophisticated, but that’s how he started,” Ghassan adds. His father also provided newspapers, magazines and literature to Tripoli’s international community including Pakistani and Bangladeshi workers. Anglophone readers would choose their reads from the bookshop’s eclectic shelves.

The problems began after the 1969 coup d’etat fronted by Colonel Muammar Gaddafi. Mohammed was banned from publishing, as the only books to be read were those penned by the dictator himself. Around 1977, Gaddafi was sidelining politicians, unions, businessmen and students. The gap was closing in on Mohammed so he followed his father’s advice to leave the country.

The house published three books in 2014: Mansour Bushnaf’s Chewing Gum; a tale of romance, but more so an existential observation of Libyan society under dictatorship. Maps of the Soul by Ahmed Fagih was first published in Arabic six years ago. The first volume is set in 1930s Libya under Italian rule, and contains the first three parts of Fagih’s monumental twelve-part work. African Titanics by Eritrean writer Abu Bakr Khaal tells the story of a young man’s struggle to European shores from Eritrean. Set to be released in April, Sudanese author Amir Tag Elsir’s Ebola ’76 is a satirical novella about the first deadly outbreak of the disease almost forty years ago.

In Summer 2015, the first volume of Alessandro Spina’s The Confines of the Shadow will be released consisting of three novels – The Young Maronite (1964), Omar’s Wedding (1970) and The Nocturnal Visitor (1972). Spina’s epic was first released in Italian in 2006 released in Italian and earned him the prestigious Premio Bagutta award in 2007.

In Summer 2015, the first volume of Alessandro Spina’s The Confines of the Shadow will be released consisting of three novels – The Young Maronite (1964), Omar’s Wedding (1970) and The Nocturnal Visitor (1972). Spina’s epic was first released in Italian in 2006 released in Italian and earned him the prestigious Premio Bagutta award in 2007.

“Charis, who translated African Titanics introduced me to Andres Naffis-Sahely who is translating the Italian original into English. I also have the rights for the Arabic version, which I intend to publish.”

“If I succeed by producing something people can appreciate and Libyans can look up to, then I have done my job. Our confidence and self-esteem about being Libyan has taken a blow, and I think we should all try to change that – the people who don’t want to pick up guns or be in positions of power. We want what is fair for us. Let’s take it one step at a time,” Ghassan tells with a ray of optimism.