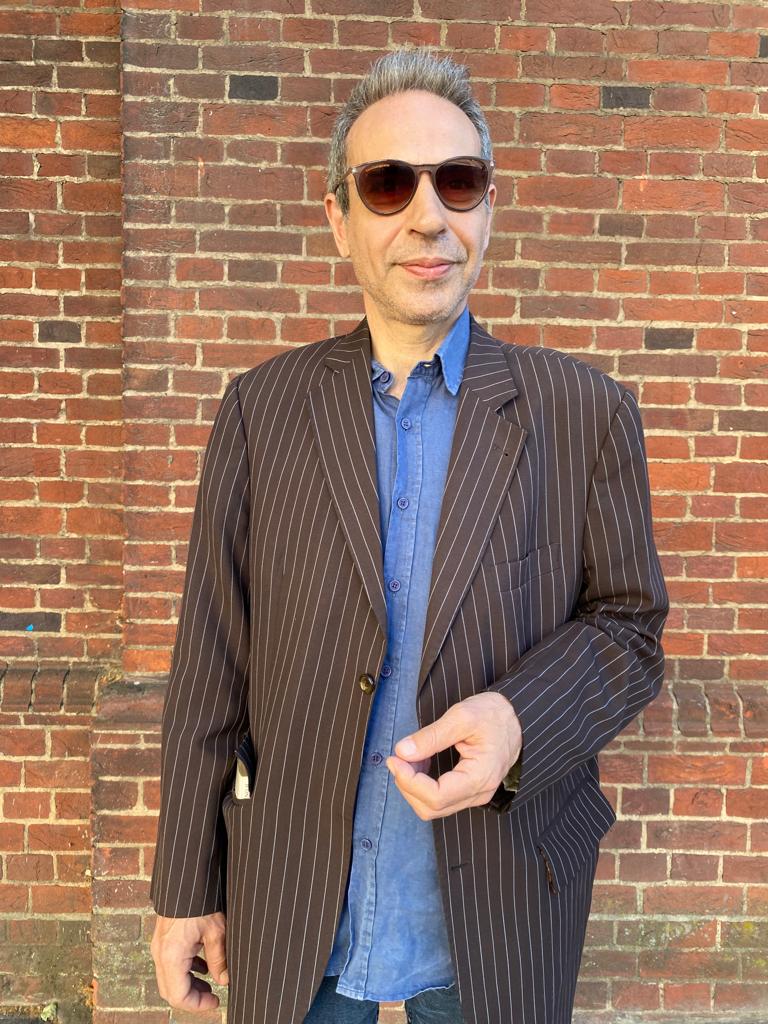

Interview with Arabic translator Raphael Cohen

Posted by Darf Publishers, August 30th 2022

Raphael Cohen translated Darf’s most recent release Flowers in Flames, a poetic novella from the award-winning Sudanese writer Amir Tag Elsir

How did you get into translating, Raphael?

Well, it was a very long time ago. I started working for Al Ahram, an English language newspaper here in Egypt, mostly as an editor. I had studied Arabic and so started contributing translations to their culture page. They ran material in translation fairly frequently in those days. This was in the early 90s. That’s basically how I started doing literary translation. I was approached by a writer in 2010 to translate her novel. She was someone I knew personally, so I translated that and it was published by the American University in Cairo. Every now and then, someone comes along and asks me to translate something and I translate it.

Did Amir reach out to you for this book?

Yes. It was shortlisted for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction (the Arabic Booker). As part of their process, a section from each of the shortlisted books, a few thousands words, is translated for the prize ceremony. And I did that. After that the author got in touch with me and asked me to do the rest of the book.

Do you do other work in literature?

Mostly translation. Occasionally I do some editing work, but no, translation mostly.

What was it about Amir’s new book that drew you in?

I think that it speaks to a current issue, this whole idea of an Islamist revolution. Its focus is on the way women are treated or have been treated, what we’ve seen in Syria or at least what we know about Syria. I think there are also big problems in Iraq and now, it seems, in Afghanistan too. It’s raising the issue around a certain extremism in Islamist thinking, which always ends up taking it out on women. The book’s an exploration of that, through the voice of its main character.

Amir’s a tricky writer because he spins a lot of tales all at the same time. Lots and lots of things are introduced, lots of characters, all very incidentally. Some characters are more fully developed, but there are lots of little incidents where you just get a scene or a person which may never appear again. All the time there are things happening, which sometimes I found a bit challenging, really.

To follow the plot?

The arc of the plot is pretty straightforward. It’s quite digressive in its way, but I suppose it’s trying to build up a picture of this place and its community and people, before and after, what happens to it, how it’s destroyed. I think that’s an image or a kind of process I’d imagine he sees as having happened in Syria, Iraq and possibly about to happen in Afghanistan.

I read Ebola 76 and I guess that runs on a similar theme of looking at a place and talking about how situations affect a whole place. What made you want to translate Arabic originally?

I studied Hebrew and Arabic at university, and then I went on to do postgraduate work in Arabic literature. I was interested in translating and I was interested in Arabic language. I spent time in Egypt when I was younger, and I’ve been living here for the last 15 years. So I’m in the culture in a certain way. I’ve always found it much easier to work in translation when I’m living in an Arabic speaking country, rather than living in the UK. I’ve never really sustained being translator in the UK. I’ve done other things in the UK, but living in Egypt I’ve focused on translation.

Is there a difficulty in trying to translate and promote an Arabic book in England?

Well, you’re promoting a book which is talking about something universal. You can look at it not as an Arabic book, but as an English book. It’s addressing an issue, which is relevant to the UK reader or an American reader, for example.

So rather than emphasising it as a Sudanese book or a translated book, it’s more universal than that?

It’s not a Sudanese book. As far as I’m concerned, it’s not really talking about Sudan in any recognisable way. You’d have to ask the author. It’s certainly set in Africa. But even historically, it’s not really clear. Ostensibly it’s set at the end of the 19th century. In terms of language, he’s not careful about bringing in modern rather than anachronistic language.

So it’s not time specific?

That’s not really part of how the book works. It’s not a historical novel.

What’s your process for translating? Do you get given a full manuscript and work through it page by page?

I read it. I know translators who don’t read through a manuscript first, they just open the book and start translating. I never do that. I always read it. Sometimes I’ll read it twice. For this one, I read it once. Even when I’m working on it, I might stop and read a whole section before translating it. Then I’ll go through and make a draft. Possibly put it aside for a little bit. Mostly it’s about time pressure. It’s always good when translating to have periods when you’re away from the text, to let it percolate. If there are things you know you want to think about, you can think about them at leisure. You may have a flash of inspiration and solve a translation problem like that. I’ll read it, get a first draft, try and work a couple of hours, maybe two two-hour sessions a day – that’s about as much as my brain will do. For the next stage I’ll go through it again with the Arabic in front of me. I may well reread the whole book. For this one, I read the first half again, and then went back to the first half with the Arabic. It helps to read through line by line and paragraph by paragraph and to look at the English and the Arabic, to make sure I haven’t missed anything. I do a bit of linguistic tweaking in English, but it’s more making sure that I’ve understood the text well, rather than focusing on the English. Then I concentrate on the translated text in its own right, allowing the Arabic original to slip into the background.

Are you translating for an English readership?

Idiomatically, I’m writing in English, not in American. My imagined reader is someone who speaks English. It’s nearly two and a half years now, since I’ve been in the UK, because of COVID. Normally, I come to the UK every year, and spend two or three months in the summer. Then I’ve got some idea about what people sound like. But I live in Arabic. I don’t speak English every day. I mean, the language is always changing, changing, changing, and I’m not fully a part of it.

Flowers in Flames is available to buy on Darf’s online store:

Flowers in Flames