The Book of Mordechai: a study of the Jews of Libya

Posted by Darf Publishers, December 14th 2017

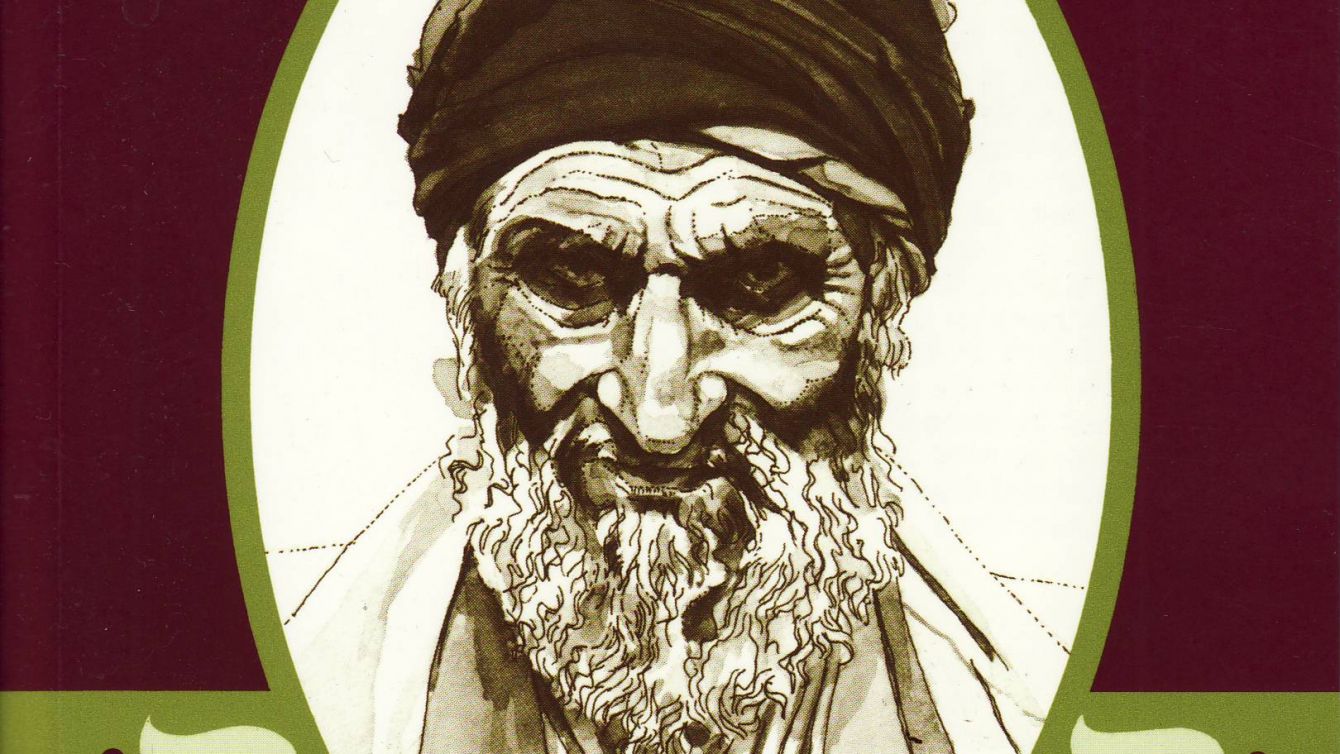

MORDECHAI Hakohen (1856 – 1929) was born in Tripoli to a Jewish family of Italian descent. His youth was deprived of a formal education like many others, however, he later studied law and worked in magistrates and Rabbinical courts in both Cyrenaica and Tripolitania. The Book of Mordechai is an accomplished anthropological study of Jewish life in Libya; a period that has drawn little scholarly attention.

Hakohen composed the book in the early years of the twentieth century, but the first Hebrew edition was not published until 1978. Editor and translator Harvey E. Goldberg released an English version in 1980, which includes concise forwards to each chapter; a feat that is not available in the Hebrew text.. The 1993 revised Darf publication covers Parts III and IV of Hakohen’s work, which Goldberg considers to be the most informative to audiences. This includes sections: ‘Economy and Language’, ‘Communal Life and Festivals’ and ‘The Italian Invasion of Libya’.

Jewish people had a lower social rank than Muslims, often referred to as dhimmi status (protected non-Muslim people in an Islamic state). Although Hakohen expresses concern over religious inequality, his observations of culture and ethnicity are objective, allowing him to draw valid parallels between differing groups who once lived side by side. The book also functions as an evolutionary linguistic analysis of North African Hebrew and Arabic, detailing the reciprocal respect between the two languages.

The Berbers, who ‘accepted the Mohammedan religion of their own free will’, also adopted a number of Jewish traits. This includes the eating kosha meat, and avoiding even numbers. Hakohen elaborates: ‘If a man eats two figs he is told to eat a third for fear of the consequences…The women wear a silver bracelet on their left arm, for they say that the left side is harsh, and silver is soft and merciful.’

‘Marriage and the Wedding’ (section 99) is a particularly colourful section of Hakohen’s study. We learn that once a young man finds his bride-to-be, she must cover ‘her face from him with the veil of shame’, which changes into the ‘veil of modesty’ when the she must express her bashfulness by running from her parent’s home to a relatives. After being unveiled, she flaunts her beauty at the ceremony, and later reveals a chicken egg from her bosom before launching it at the groom’s room. This is to remind the Jews of the destruction of the Temple.

In ‘The Geographic and Historical Setting’ (section 90), he reveres in the beauty of Jebel Nafusa, a northwestern mountain range in Tripolitania, but remains firmly grounded in his position as an anthropologist.

“There are many hills with ruined cities, and an air of antiquity hovers over them. However,the extent of destruction testifies to the size of the former settlement. There is still a ruined cave in Jado, and local tradition holds that it was once the synagogue of the Jews. Jewish cemeteries can also be found there, but now most of them are farmed by the Berbers.”

Hakohen is consistently objective in his cultural and ethnic observations. This allows him to draw valid parallels between these groups who once lived side by side. When Goldberg spoke to his daughters years later, they said Hakohen ‘became more and more removed from daily affairs, and was primarily concerned with making an important contribution to science.’ They believe it was his commitment to solving the mysteries of the physical world that resulted in a fatal stroke on August 22, 1929. Although it was almost 50 years later when the text reappeared, ‘The Book of Mordechai’ is now established as an accurate documentation of Jewish culture in Libya.