The Magic Gate of the Sahara

Posted by Darf Publishers, December 18th 2017

First published in the early 1930’s, Angelo Piccioli’s La porta magica del Sahara (The Magic Gate of the Sahara) presents a colonial vision of Italy’s ‘fourth shore’. This guide around Tripolitania takes the reader on a sensuous journey through a land that was supposed to be the future of Italian agriculture and tourism at the height Mussolini’s fascist reign.

Riddled with colonial snobbery, Piccioli’s travelogue describes Libyan culture as little more than a ‘primitive simplicity of life’. Our guide acknowledges and appreciates its dynamical make-up of Judaism, Islam, Arabs, Berbers, Turks and Europeans, but he’s cynical as to whether they can invigorate the fertility of a land once ruled by the Greeks and Romans. The Italian Empire was the rightful heir to Libya, and would pride itself on restoring civility in place of what was then conceived as a wretched, barbaric culture.

As much as Italy wanted Libya, Piccioli ultimately argued that Libya needed Italy. Throughout the text, he describes the expansive projects being undertaken where fruit, olive and almond groves were transforming Libya into a vast land of cultivation. Roads were being constructed to link towns and cities that were mere caravan routes beforehand. Modernity was beginning to bridge the northern tip of Africa and the boot of Europe A cross-cultural rites of passage.

As much as Italy wanted Libya, Piccioli ultimately argued that Libya needed Italy. Throughout the text, he describes the expansive projects being undertaken where fruit, olive and almond groves were transforming Libya into a vast land of cultivation. Roads were being constructed to link towns and cities that were mere caravan routes beforehand. Modernity was beginning to bridge the northern tip of Africa and the boot of Europe A cross-cultural rites of passage.

Piccioli speaks in awe of Tripoli’s most prominent structure, the Arch of Marcus Aurelius: ‘[it] takes us back into history and into the midst of our own Italian civilization. Its vigorous, square, Latin pile stands out like a symbol, facing the sea, amongst the untidiness and triviality of the Oriental peoples who, through all the centuries, have never been able either to spoil it or bury it. It is like a symbol of warning.’

The reader is being convinced that Italy were to be the savior of North Africa; the restorative force that would pick where an ancient empire left off. Oblivious to what lied in store for the Empire, our guide aimlessly wanders Tripoli’s souqs and streets, both amazed and fascinated by the cultural practices taking place around him. One of his finest storytelling moments is when recounting the ‘Nocturne at Shara Zawia’ – a sort of satirical dance on sexual desire taking place in a space overwhelmed by tobacco-smoke and fumes of benzoin. We are sat amongst Bedouins and locals, mesmerized by this dancing lady, ‘sensual pleasure personified, disquieting and threatening, strong as death.’

On the subject of art, Piccioli criticises Arabian geometrical work for its simplicity. The intricacies of European art would always be a superior form that required deconstruction. Aesthetically, he admires the art he experiences whilst travelling around Tripoli. However, in line with his monolithic perception of the indigenous people, this type of art was monotonous, and belonged to a race who ‘suffers from stagnation of spirit’. The enlightened Italians were all about ‘progression’, and Piccioli was a crusader for the abandonment of tradition in exchange for modernity

The Magic Gate of the Sahara comes to life once our guide leaves the coast, and heads south into the desert. The wheels of the Fiat are guided to tiny villages and oases by camel footprints and instinct. They visit natural wonders like the Hammada El Homra – a vast, arid part of the desert, and Dirj – a town that from a distance Piccioli admires, but becomes relatively disappointment upon entry: ‘…as one approaches its proportions gradually diminish; the picture falls to pieces and all that remains is a mass of ruined houses, all dismantled as though they had undergone a siege – burnt up, arid, abandoned, one might almost say invaded by the solitude of the desert.’ It is in the solitude of the Sahara where he becomes spiritually enlightened, overwhelmed by nature in its entirety.

Part III visits the Western border town of Gadames: ‘In few places on earth, I believe, is one dominated, as at Gadames, by that singular charm which is exercised by traces of a vanished waty of life, of a world that has lasted from immemorial times. Everything here has been as it is for centuries; and perhaps everything will remain so for countless more years.’

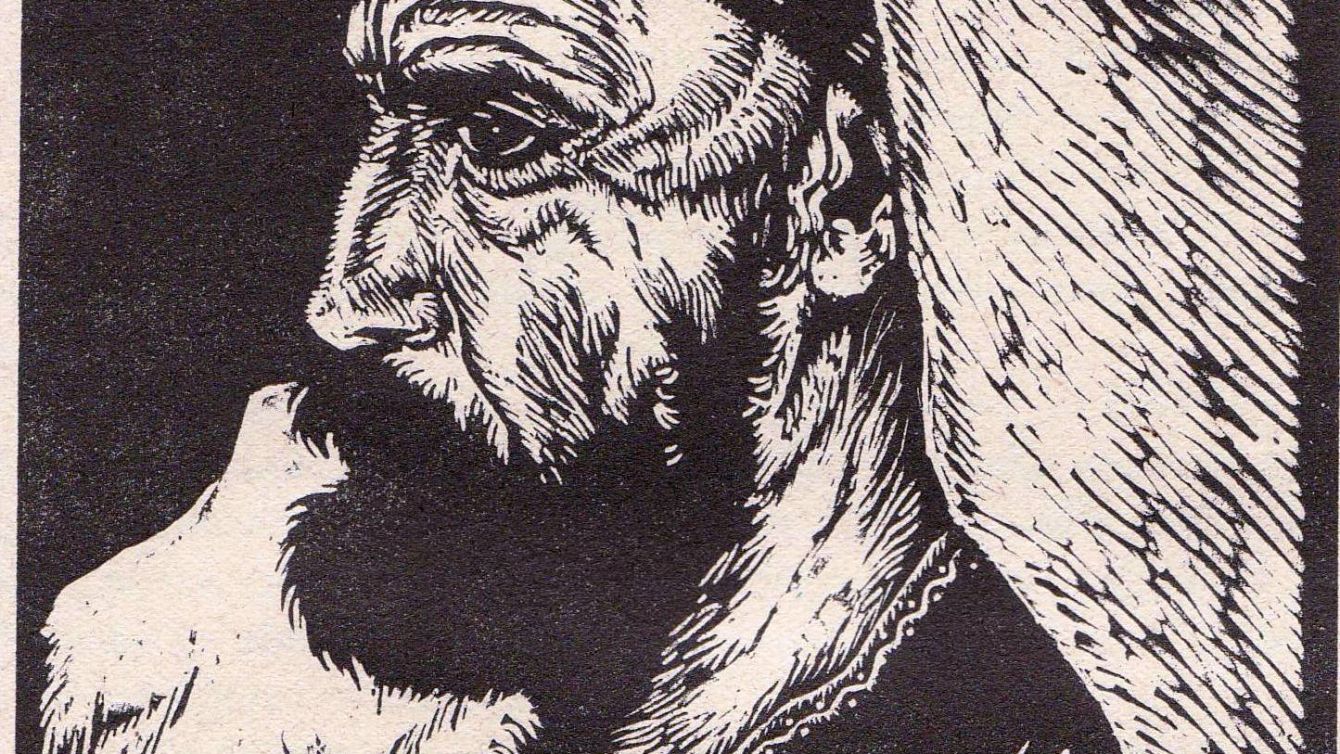

It is here where Piccioli contemplates the different pace of life between the Arabs and Europeans, and understands why there is ‘no reason why that which has been should cease to be: stability of custom has no limit but the end of the world itself.’ Perhaps Gadames stirred a feeling of admiration towards simplicity over the incessant life of Europeans. Through the beautiful illustrations of the original, and photographs included in the translation, one can see how a foreigner would be absorbed by the tranquility and mysticism of Gadames; a desert fortress protecting its inhabitants from the relentless Saharan sun.